Weird-ass Optimization Function

Raw material from the book that may not make the final cut

Here’s a super fresh, raw, just fished out of my brain section from chapter 3 of Value of Nothing. Read it aloud last night and was told, “maybe kinda boring?” So I tightened it up and add a curse word. How does it rate?

The Price is … Not what you think

Let’s take a minute to think about movie ticket prices.

The average ticket price in the mid-70s was two bucks and a quarter. This was a time before megaplexes, so most theaters had two screens. Small towns were lucky to have one. What happened when interest in seeing a movie was much larger than the limited supply of seats? Technically, what should happen is that when demand for a good (whether it’s a movie ticket or a plastic toy) rises, a new equilibrium will be achieved with higher prices and a larger volume of goods exchanged. But in the 1970 movie industry, supply was limited to a relatively scarce number of seats, plus the price was set and unvarying. In that case, the market “fails” and allocation happens not at the equilibrium but at the pre-set price point -- lots of consumers can pay cash, so the winners pay with something else. Time. Those willing to spend hours in line, paid with their time. For rare movies like Star Wars, the queue would extend far outside of the theater, down the street, and even around the block. This is where the term blockbuster comes from.

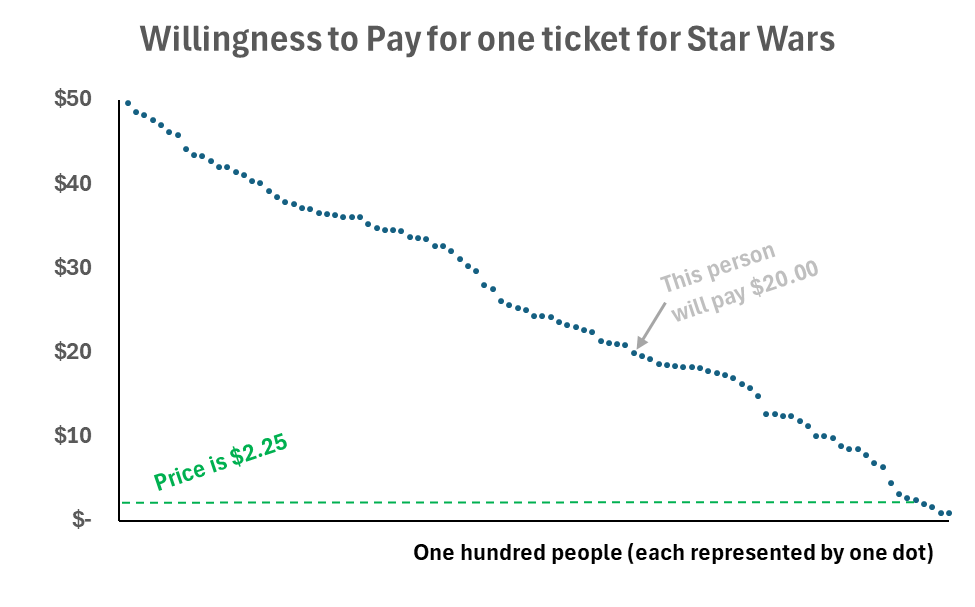

What’s interesting is that instead of paying with time, everyone in line was willing to pay with more cash than the sticker price, and probably lots more. To illustrate the point, imagine a neighborhood with 100 people who have an opportunity to see Star Wars. Each one has an amount they are willing to pay (which we will call their WTP) that is unique to them. The following chart puts the 100 values in order from highest to lowest, generated randomly in Google Sheets between zero and a maximum of $30. You can see that the 100 dots look like a downward-sloping line, with 96 of the 100 WTPs above the price line.

Suppose that Sam had a $20 WTP to see the film. That means when Sam pays $2.25 he also gets what economists call “consumer surplus” to the tune of nearly eighteen bucks. That’s the magic of exchange. Any time any person buys any thing for cash, they also get some amount of this magical surplus.

The point seems obvious, but it’s worth keeping in mind because consumer surplus is one of the deep truths in the world of economics. Each of the dozens of purchases you make on a daily basis comes with surplus. If you have a choice between (A) a $5 Wendy’s hamburger and (B) a $5 platter with a steak, a lobster, and five burgers, you know there’s a whole lot of consumer surplus on that B platter. More seriously, whenever you spend money on something, you know in the back of your head that you could spend it on a hundred different things. Instead of buying that five dollar Wendy’s burger, what else could you buy? Five dollars of fries. Five dollars of gasoline. Five dollars of chewing gum. Five dollars of pens at a nearby Target. The list isn’t infinite, but it’s close. What your brain did when getting the Wendy’s burger was instinctive but also a profoundly intricate computation of maximizing your surplus, or what Spock calls “utility maximizing.”.

A skeptic would scoff -- No, I just don’t have time to think of all the options, that’s all I was maximizing. And they’re right, but not for the reason they think. Maximizing utility is a very deep-brain function of the human subconscious. It’s just like the deep geometry that professional athletes do every time they shoot a basketball from 36.34 feet (versus 36.12 feet) when their left ankle is gimpy and the ball is 14 percent slicker than normal. Our brains are amazing, and they do millions of computations under the surface. When it comes to economic behavior, you’re Utility Maximizing with more neurons than breathing, and you’re doing it constantly, with a weird-ass optimization function whirring somewhere in the neocortex that, yes, includes an allocation of the scarce compute time involved, too.

A very thought provoking article. Being an old sailor, I am reading the article for the second time! Guess that's what I need to understand real journalism. Once again, thank-you.

I had to read it twice too. I skimmed it the first time, decided it had potential, and came back later to read it again, this time with intention.

Being an objective realist and an engineer/scientist I was wondering, “How can I apply this? What is the daily application?” Still, I found myself agreeing.